The Strong Black Woman: A Dangerous Myth

- jonetta rose barras

- Aug 17, 2021

- 6 min read

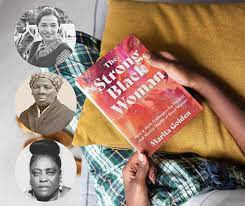

THE STRONG BLACK WOMAN: How a Myth Endangers the Physical and Mental Health of Black Women

By Marita Golden

(Mango Publishing 2021)

pp-192

THE motivation for award-winning author Marita Golden’s latest book, The Strong Black Woman: How a Myth Endangers the Physical and Mental Health of Black Women, may have been the coronavirus pandemic. She admits that it was written during the spring and summer of 2020, when all of us were grappling with a giant unknown that was massively upending our lives.

It also could have been animated by the heartache, anger, and upheaval surrounding the public and high-profile murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black and Brown folks at the hands of white police officers. Sustained and widespread national and international protests over Floyd’s murder elevated the issue of racism, including institutional racism, leaving many ordinary white citizens in the country pledging to demand improvement in the treatment of Blacks and other people of color in America.

Actually, it was all of that and more. In her book, Golden, expertly and brilliantly, locates the intersection between those tragedies: the Black woman.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in 2020, during the early months of the pandemic, that Black women were among the hardest hit: They died in large numbers from COVID-19; disproportionately suffered stress and mental health disorders; and carried the economic burden, holding families together, often without sufficient resources or government support.

During his final minutes, Floyd cried out for his mother. Breonna Taylor was one of more than 200 Black women killed by police between 2015 and 2020, according to the Washington Post.

Golden blends those political and current events to create a rich, broad, deep and inventive narrative. She explores the ramifications of the label “The Strong Black Women.”

Burned into the forehead, arms, eyes, mouths and legs of Black women, that branding may seem a descriptive celebration of the fierceness of the sisterhood. It is that. Equally important, however, it is a bruising and a scaring. It is a weight that prevents Black women from publicly declaring their truth. It instigates harmful mask wearing and deprives them the opportunity to heal and love themselves--even as they offer ample servings to others.

“The Strong Black Woman” is simultaneously memoir, meditations, interviews and reimagined conversations. Golden guides readers through history, across varied landscapes—sometimes roughed and dark--and myriad narratives to explain why Black women must divest themselves of the term—or at the very least redefine it.

The journey begins with her own story: the discovery that unknowingly she had suffered two strokes. Her husband had “two small strokes with heart attacks in the last two years,” she acknowledges. He also is a “24-year survivor of non-Hodgkin lymphoma; and “lives with Type-2 diabetes.”

She, however, is a profile of sound health—at least that’s what she thought. No diabetes, same weight as when she was in college, eats healthy, meditates daily. No one even believes she soon will turn 70 years old, she boasts.

That may be why she could hardly believe her primary physician’s diagnosis that she had suffered not one but two strokes. Her body misbehaved despite the regimen on which she placed it.

Before that revelation Golden was part of the Black-don’t-crack-chorus. Now, there were tons of questions: “Who was I? What else was my body doing? Apparently Black did crack,” she writes.

Had it always cracked? Had she engaged in pretense? Had she not just neglected her wellbeing but also recklessly endangered her life? Equally important, was she alone. How many other Black women each day were walking Strong Black Women marques, failing to appreciate the signs of deterioration or the dangers they were inviting?

" Our bodies souls and spirits are a map, a testimony to the ravages of our enslavement, the cruel legacy of legal segregation and lack of access to wealth, good employment, stable housing and good health care. And our psyches have been twisted and turned inside out by the stories we tell ourselves. And the stories that are told about us. Stories that have sometimes saved and sometimes sabotaged us. The Strong Black Woman. The Angry Black Woman., The Black woman who says yes to everyone but herself. The Black woman who believes Jesus and only Jesus is the answer to every problem, who rejects the idea that therapists, doctors, self-care are also part of Jesus’ plan. The Superwoman. The Invincible Superwoman. We’ve had to be strong. We have good reason to be angry. We say yes over and over to our families because the world so often tells them no.

And who wouldn’t want to be a Superwoman."

Who, indeed?

Golden may have inherited “The Strong Black Woman” persona, replete with regular mask-wearing, from her mother—a domestic worker with the uncanny luck of winning the lottery

enough times that she had money to purchase several houses where she rented out rooms. Her fortunes with men weren’t so great, however. She married three times; the first husband, about whom Golden only learned about after her mother’s death at 63 from a stroke and heart disease, was left in South Carolina. The second husband was an alcoholic who eventually was admitted to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. The third, Golden’s father, was a Cuban-cigar-smoking, taxi-driver and womanizer. He died at 62 years old.

Despite, the difficulty of life in segregated Washington, DC in the 1950s and 1960s, Golden says she never saw her mother cry—not once. That became Golden’s operational principle.

"I was twenty-one years old, and my mother was dying. She lay comatose in a bed in a rehabilitation center for six months, wasting away before my eyes. I was a raise the Black power fist, Afro-wearing, militant activist and a B-plus average student We Wear the Mask attending American University, and I had already started wearing the mask. The Strong

Black Woman mask.

" During the agonizing months of my mother’s illness, death, and the grieving that followed I told only one person what I was going through. My best friend. Louise and I had attended Washington DC’s Western High School together where we worked on the student newspaper and shared our plans for life after high school, life after college, life as grown women. At American University we studied Philosophy, English, Science and discovered love and sex and heartbreak with boyfriends returning to the US after a stint in the Peace Corps or who were from an African nation we had read about in books and hoped to visit one day. We became young women. We became young Black women. Together. Louise was the only person with whom I didn’t wear the mask."

THE default was set. It was deployed when Golden's marriage to a Nigerian fell apart, after she had moved to his country and given birth to a son. It was deployed when she arrived back in the United States unsure of her next steps but determined to “handle her business.”

"The Strong Black Woman Syndrome, which requires that Black women perpetually present an image of control and strength is a response to combination of daily pressures, and systemic racist assaults. As we live and deal with racism and sexism, the Strong Black Woman response becomes an automatic response. We see this as strength. The world

does too. Buttressed and buffeted sometimes from all sides, we go on, move on, tapping

down suffering and complaint. But the price must be paid. The Strong Black Woman

syndrome silences the healthy and necessary expression of pain and vulnerability.

Like Golden, I masqueraded through much of my early life, refusing to allow others to see my pain, to understand the innerworkings of my soul. In my book “Whatever Happened To Daddy’s Little Girl? The Impact of Fatherlessness on Black Women, I codified the Fatherless Daughter Syndrome in five factors. One of the tell-tale signs was the Over-Factor, which involved overcompensating. I wrote that fatherless daughters present ourselves as capable of doing all things for all people all the time. We leap tall building and damn-near kill ourselves.

Golden gathers other women voices to provide the cautionary tale of The Strong Black Women Syndrome. There are Black women physicians, therapists, professors and just ordinary people who share their narratives. She also masterfully uses the dead, including Harriett Tubman, Rosa Parks and Fannie Lou Hamer. Zora Neale Hurston’s words and those of selected characters from her books come to the circle, including Janie from Their Eyes Were Watching God:” “She starched and ironed her face forming it into just what people wanted to see.”

I found myself wishing there weren’t so many other voices. That is a minor complaint, however.

An exquisite writer and storyteller, Golden provides a book that is fresh, creative and worth reading while plotting a course for the next stage of Black women’s liberation and freedom.

Comments